Memories are not always precisely what happened. They may change over time, and each person has different memories of different events. Memory is suggestive, meaning that the opinions and recollections of others are likely to influence what a person remembers. Therefore, the existence of standard false information may subtly affect personal memories and form conspiracy theories and fraudulent and harmful beliefs. False beliefs about the death of Nelson Mandela are a famous example of this phenomenon. In this article, we explain the wonder of the Mandela effect and introduce other models. Finally, we will explain the causes of this problem and the methods of detecting false memories. So if you think you have ever experienced something like this, stay with us until the end of the article.

What is the Mandela effect?

The Mandela effect refers to a situation in which many believe an event has occurred when it has not. This includes when people misremember a historical event or figure.

When was the term Mandela effect coined?

This term was first coined in 2009 by Fiona Broom. At that time, he created a website to describe his observations in this field. Broom was speaking at a conference about the tragic death of former South African president Nelson Mandela in prison in the country in the 1980s. This was even though Mandela did not die in prison in the 1980s but in 2013. When Brom started talking about his memories with others, he realized he wasn’t alone. Others had seen the news coverage of his death and his wife’s speech.

Broome was amazed that such a crowd could remember an event that had never happened in such detail. Encouraged by the publisher of his book, he created a website to discuss what he called the Mandela Effect and other incidents like it.

Why does the Mandela effect happen?

Memory is very flexible and malleable. Information from others can alter our memories, causing us to misremember events or remember events that never happened. This phenomenon may have five reasons.

1. False memories

The most likely reason for Mandela’s work is these kinds of memories. Before we explain what false memories mean, let us look at an example of Mandela’s work. This helps us understand how memory can go wrong and lead to the phenomenon we are discussing.

Do you know who Alexander Hamilton was? Most Americans learned in school that he was one of the founding fathers of the United States of America but not its president. However, when you ask this country’s people for their presidents’ names, many mistakenly assume that Hamilton was also the president. Why?

Suppose you want a simple explanation of this problem in the language of neuroscience. In that case, the memory of Alexander Hamilton is encoded in the area of the brain where the memories of the presidents of the United States are stored. How memories are stored is called the “neural trace,” The framework in which similar memories are linked together is called the “mental schema.” So to put it simply, when people try to remember Hamilton, their neurons become more closely connected and bring the memory of presidents with them.

Researchers have discovered a more straightforward way to induce false memories, which they named the Dies-Roediger-McDermott model. In examining this model, participants are given a list of related words, such as:

- zebra;

- Monkey;

- whale;

- hit

- fail.

After reading the list, they are asked if they can remember the word “bait.” Usually, the participants in this experiment recognize the bait word and remember reading it, even though it was not on the list.

2. imagination

Daydreaming means that your brain fills in the gaps in your memories to understand them better. Daydreaming is not lying but remembering details that never happened. This problem worsens with age.

For example, someone who does not remember what happened to Nelson Mandela may conclude that he died long ago. As a result, he says that he reflects on this “fact.” He is not lying, and he believes in his false memory.

Daydreaming is a common symptom of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s or dementia that affect memory. When someone with dementia talks about something that did not happen, they are not lying or trying to deceive someone. He doesn’t have the information or awareness to recall a particular memory or event.

3. Having a background

In psychology, having a background means exposure to a direct stimulus affects a person’s reaction to the next push. This phenomenon is also called suggestibility or default. For example, if a person reads or hears the word “grass,” he will recognize another related word, such as “tree” or “lawmaker,” much faster than an unrelated word.

Foregrounding uses seduction techniques to arrive at a specific response. For example, “Did you take the red ball from the shelf?” Much more tempting than the question, “Did you take anything off the shelf?” Is. The second question is general, but the first describes picking up a specific object, the “red ball.” Therefore, the effect of the first question on memory is more significant than the second.

Memories are vulnerable information stored in the brain that may change over time. We think our memories are accurate, but they are not necessarily so.

4. Misleading information after the event

The information you get after the event can change your memory. This information includes event details. This issue makes the testimony of eyewitnesses unreliable.

5. Alternate realities

Another reason they cite for the Mandela effect comes from quantum physics and relates to the idea of parallel universes. Accordingly, there may be parallel realities or universes that are interwoven with our universe’s timeline. In theory, this would cause a group of people to have the same memories because the timeline has been altered by shifting different realities from the two universes.

There is no reason to reject this theory, and there is no way we can deny the existence of a parallel universe. For this reason, such a theory about Mandela’s effect is still interesting. You cannot prove that a real parallel universe does not exist. So you can’t ignore its possibility. However, many people like to have a little mystery and excitement in their everyday life.

The role of the Internet in the phenomenon of the Mandela effect

The role of virtual space in influencing collective memories should not be underestimated. It is not a coincidence that attention to the phenomenon of the Mandela effect has increased in the digital age. The Internet is a powerful way to spread information; misconceptions and false beliefs will likely be formed with this information. Then groups are formed that support these beliefs. What was once only people’s imagination finally seems natural.

According to an extensive 10-year study on 100,000 news items discussed on Twitter, the probability that news hoaxes and rumors will win over the truth is 70% higher every time. This victory was never the result of manipulation or bot activity but the verified accounts of real people responsible for spreading more misinformation than truth.

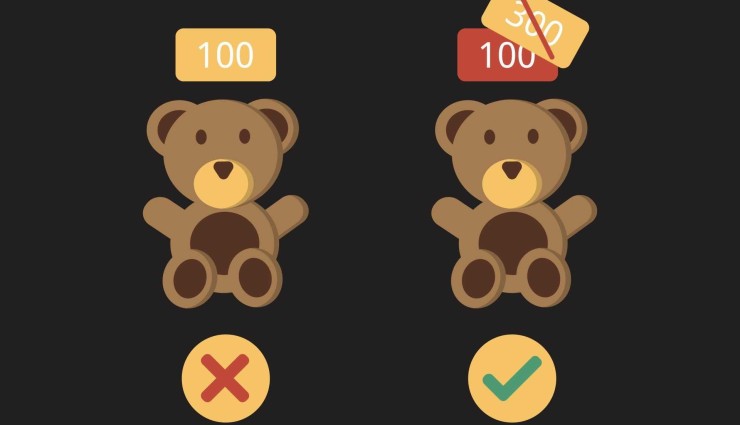

Such an idea of the speed of spreading false information in cyberspace can explain Mandela’s effect well. The Internet is a powerful tool for spreading false memories and beliefs. Some websites use these techniques to convince people that things have happened that never happened. Some of these techniques are:

- having a background;

- combining false information with factual information;

- repeating a false claim over and over until it seems true;

- They are spreading fake news to support a false claim.

Examples of the phenomenon of the Mandela effect

1. Henry VIII eating a turkey leg

People remembered a painting of Henry VIII eating a turkey leg. Although such a board does not exist abroad, cartoons similar to it have been made.

2. Luke! I am your father

If you have seen the fifth part of the movie “Star Wars,” you probably remember Darth Vader saying the famous line, “Luke! I am your father.” utters In that case, you might be surprised to learn that the sentence read: “No, I’m your father.” Most people remember the first sentence rather than the second.

3. Mirror! O mirror on the wall

If you have seen the cartoon “Snow White and the 7 Dwarfs”, you probably remember this sentence: “Mirror! O mirror on the wall! Who is the most beautiful?” You might be shocked that this dialogue begins with the words “The magic mirror on the wall.”

4. Location of New Zealand

Which side of Australia is New Zealand? If you look at the map, you will notice that it is located in the country’s southeast, but some people claim that New Zealand is in the northeast of Australia, not in the southeast.

The method of detecting false memories

One of the problems with false memories is that they look like real memories. You may have a lot of confidence in your memory and automatically makeup details to support it. You may not have any external evidence or claims to prove a memory false. In this case, you can increase your chances of identifying the true from the false through one of these methods:

- I use reliable sources such as encyclopedias, news sites, or magazines.

- Consider the possibility that you remember this memory because someone else does.

- We seek independent evidence to support memories that are suspect or likely to be traumatic memories.

final word

The Mandela effect is the false memory of everyone that many people or a group of them believe. These memories may not be harmful, but sometimes they help form conspiracy theories or political schemes.

Memory is not a complete record of past events. It may change with time and with the background. If the only reason to prove a coincidence is individual observation, there is a possibility that it did not happen. Independent verification of collective memories, especially those with significant social or political implications, can reduce the likelihood of disinformation and conspiracies spreading.

Warning! This article is only for educational purposes; to use it, it is necessary to consult a doctor or specialist.